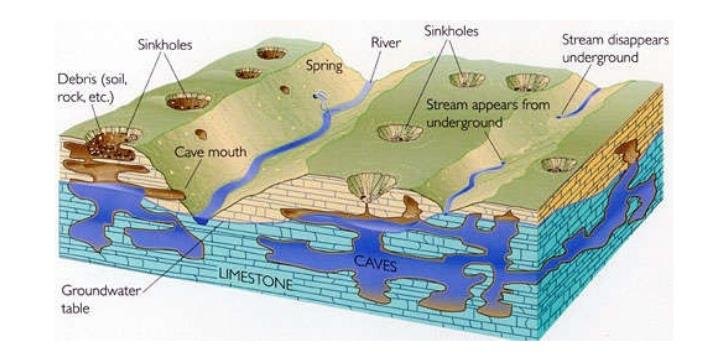

10/4/2021 Karst Topography

is characterized by barren, rocky ground, caves, sinkholes, underground rivers & the absence of surface streams & lakes. It results from the dissolving effects of groundwater on limestone. Limestone dissolves fairly easily in slightly acidic water, which occurs widely in nature. Rainwater percolates along both horizontal & vertical cracks, dissolving the limestone & carrying it away in solution, creating caves & sinkholes, like Ontario's Bonnechere Caves and Central Pennsylvania's Penn Caves.

Light Pollution Map / World Atlas 2015

The New World Atlas of Artificial Sky Brightness, Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences at the University of Colorado Boulder

View 3D Globe version of this map (Chrome may not be supported)

The Bortle Dark Sky Scale

The Geological Map of the Artic: Geological Survey / Commission Géologique Canada [ @GSC_CGC on twitter ]

A different view of the world! The Geological Map of the Arctic. This circular map has the North Pole in the centre, and shows the geology of everything above the Arctic Circle. Download yours free of charge here:

10/26/2021 At the U.N. Climate Summit, Could India Become a Champion, Not Just a Casualty, of the Crisis? By Raghu Karnad, The New Yorker

Modi has a desire for global prestige, for the country and for himself, and a barely hidden ambition to eclipse Nehru as the icon of modern Indian statesmanship. For the former, he will need to turn the country’s hollow, histrionic debates over nationalism toward the real end of advancing national interest, survival, and renewal in ecological terms. And, to outshine his rival of seventy-five years ago, he will need to help preside over the end of an unjust, unsustainable global order.

If the nation’s call to leadership in the twentieth century was decolonization, in this century it is decarbonization.

10/25/2021 Where Have All the Insects Gone? By Elizabeth Kolbert, The New Yorker

The significance of the theory extended well beyond actual islands. Through logging and mining and generalized sprawl, the world was increasingly being cut up into “islands” of habitat. The smaller and more isolated these islands, be they patches of forest or tundra or grassland, the fewer species they would ultimately contain. Wilson had moved on to new research questions, and initially didn’t concern himself much with the implications of his own work. When the first surveys of deforestation in the Amazon appeared, though, he was, in his words, “tipped into active engagement.” In an article in Scientific American, in 1989, he combined data on deforestation with the predictions of his and MacArthur’s theory to estimate that as many as six thousand species a year were being consigned to oblivion. “That in turn is on the order of 10,000 times greater than the naturally occurring background extinction rate that existed prior to the appearance of human beings,” he wrote.

Since 1989, South America has lost at least another three hundred million acres of tropical forest, and Southeast Asia has experienced similar losses. In places like the U.S. and Britain, which were deforested generations ago, the hedgerows and weedy patches that once provided refuge for insects are disappearing, owing to ever more intense agricultural practices. From an insect’s perspective, Goulson points out, even fertilizer use constitutes a form of habitat destruction. Fertilizer leaching out of fields fosters the growth of certain plants over others, and it’s these others that many insects depend on.

Avoiding a ‘Ghastly Future’: Hard Truths on the State of the Planet, by Carl Safina, Yale School for the Environment, 1/27/2021

Within the lifetime of anyone born at the start of the Baby Boom, the human population has tripled. Has this resulted in a human endeavor three times better — or one-third as capable of surviving? In the 1960s, humans took about three-quarters of what the planet could regenerate annually. By 2016 this rose to 170 percent, meaning that the planet cannot keep up with human demand, and we are running the world down.

“In other words,” say 17 of the world’s leading ecologists in a stark new perspective on our place in life and time, “humanity is running an ecological Ponzi scheme in which society robs nature and future generations to pay for boosting incomes in the short term.”

Underestimating the Challenges of Avoiding a Ghastly Future, by Corey J. A. Bradshaw, Paul R. Ehrlich, Andrew Beattie, Gerardo Ceballos, Eileen Crist, Joan Diamond, Rodolfo Dirzo, Anne H. Ehrlich, John Harte, Mary Ellen Harte, Graham Pyke, Peter H. Raven, William J. Ripple, Frédérik Saltré, Christine Turnbull, Mathis Wackernagel and Daniel T. Blumstein, Frontiers in Conservation Science, 2021/1/13

We summarize the state of the natural world in stark form here to help clarify the gravity of the human predicament. We also outline likely future trends in biodiversity decline (Díaz et al., 2019), climate disruption (Ripple et al., 2020), and human consumption and population growth to demonstrate the near certainty that these problems will worsen over the coming decades, with negative impacts for centuries to come. Finally, we discuss the ineffectiveness of current and planned actions that are attempting to address the ominous erosion of Earth's life-support system. Ours is not a call to surrender—we aim to provide leaders with a realistic “cold shower” of the state of the planet that is essential for planning to avoid a ghastly future.

Freshwater and marine environments have also been severely damaged. Today there is <15% of the original wetland area globally than was present 300 years ago (Davidson, 2014), and >75% of rivers >1,000 km long no longer flow freely along their entire course (Grill et al., 2019). More than two-thirds of the oceans have been compromised to some extent by human activities (Halpern et al., 2015), live coral cover on reefs has halved in <200 years (Frieler et al., 2013), seagrass extent has been decreasing by 10% per decade over the last century (Waycott et al., 2009; Díaz et al., 2019), kelp forests have declined by ~40% (Krumhansl et al., 2016), and the biomass of large predatory fishes is now <33% of what it was last century (Christensen et al., 2014).

9/8/2020 Canaries in the Coal Mine, by Amelie Bonney, Gale Ambassador at the University of Oxford

USGS National Water Dashboard

View over 13,000 YSGS real-time stream, lake, reservoir, precipitation, water quality & groundwater stations in context with current weather and hazard conditiont.

9/28/2021 Protected Too Late: U.S. Officials Report More Than 20 Extinctions, by Catrin Einhorn, The New York Times

The animals and one plant had been listed as endangered species. Their stories hold lessons about a growing global biodiversity crisis.

"When you can't get ice at the Canadian border, how much farther north can you go?"

6/29/2021 How Weird Is the Heat in Portland, Seattle and Vancouver? Off the Charts, by Aatish Bhatia, Henry Fountain and Kevin Quealy, The New York Times

Karin Bumbaco, Washington’s assistant state climatologist, said that any definitive climate-change link could be demonstrated only by a type of analysis called an attribution study. “But it’s a safe assumption, in my view, to blame increasing greenhouse gases for at least some portion of this event,” she said.

3/25/2021 What Killed These Bald Eagles? After 25 Years, We Finally Know, by Sarah Zhang, The Atlantic

In an extraordinarily exhaustive new study, scientists have pinpointed the cause of death for those bald eagles in Arkansas. No wonder the mystery took 25 years to solve: The birds died because of a specific algae that lives on a specific invasive water plant and makes a novel toxin, but only in the presence of specific pollutants. Everything had to go right—or wrong, really—for the mass deaths to happen. This complex chain of events reflects just how much humans have altered the natural landscape and in how many ways.

The team wondered if lab-cultivated cyanobacteria were somehow different from wild ones. But how? Niedermeyer went back to samples collected in the lakes, using a sophisticated technique called AP-MALDI-MSI—“like taking a picture but you don’t detect light but molecules,” he says—which revealed a novel molecule found only in the cyanobacteria growing on the hydrilla. The lab-grown cyanobacteria did not have it, nor did hydrilla by itself.

What’s more, this molecule had a formula never seen before, and, unusually, it contained five atoms of the element bromine. So the team tried adding bromine to its growing cyanobacteria. Lo and behold, the same strange molecule appeared, and this new batch of cyanobacteria caused the brain lesions in chickens. Another group of collaborators confirmed the team’s work further, by finding the cyanobacteria genes likely responsible for synthesizing the toxin. The team ultimately named this toxin aetokthonotoxin, “poison that kills the eagle.” Twenty-five years later, it finally had a name.

There are still more puzzles to solve. Where is the cyanobacteria getting the bromine? The element is relatively rare in fresh water, but Wilde says that hydrilla seems to sequester it. The concentration in the plant is 300 times higher than in the water column. How bromine is getting into the lakes in the first place is another mystery; the study authors suggest that it could be from, ironically, from herbicides used to kill the invasive hydrilla.

1/3/2021 Michigan's Warming Winters are a Big Problem for Winter Festivals, by Keith Matheny, Detroit Free Press

Michigan's cold, snowy winters, and a way of life built around them, are being disrupted by climate change. And for winter festivals reliant on cold, snow and ice — and communities reliant on the economic boost at a slow time that those festivals bring — it's causing some scrambling to adapt, and even to survive.

The Great Lakes region has seen a larger increase in annual average temperatures than the rest of the continental U.S. And "winters are getting warmer more quickly than the summers are," said Richard Rood, a professor in climate and space sciences and engineering at the University of Michigan.

"The planet overall is warming, but states like Wisconsin, Michigan and Illinois are getting warmer, faster," said Don Wuebbles, a professor in the Department of Atmospheric Sciences at the University of Illinois.

12/29/2020 Could Covid lockdown have helped save the planet? by Jonathan Watts, The Guardian

When lockdown began, climate scientists were horrified at the unfolding tragedy, but also intrigued to observe what they called an “inadvertent experiment” on a global scale. To what extent, they asked, would the Earth system respond to the steepest slowdown in human activity since the second world war?

Environmental activists put the question more succinctly: how much would it help to save the planet?

12/26/2020 The Darkest Timeline, By Jonah Engel Bromwich, The New York Times

Two years ago, “Deep Adaptation” made people confront the end of the world from climate change.

Other high-profile papers, like “Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene,” also from 2018, and Timothy Lenton’s overview of tipping points, published in Nature the following year, have galvanized the climate movement. But this self-published paper, “Deep Adaptation: A Map for Navigating the Climate Tragedy,” had a different, more personal, feel.

Does it matter if it’s not correct?

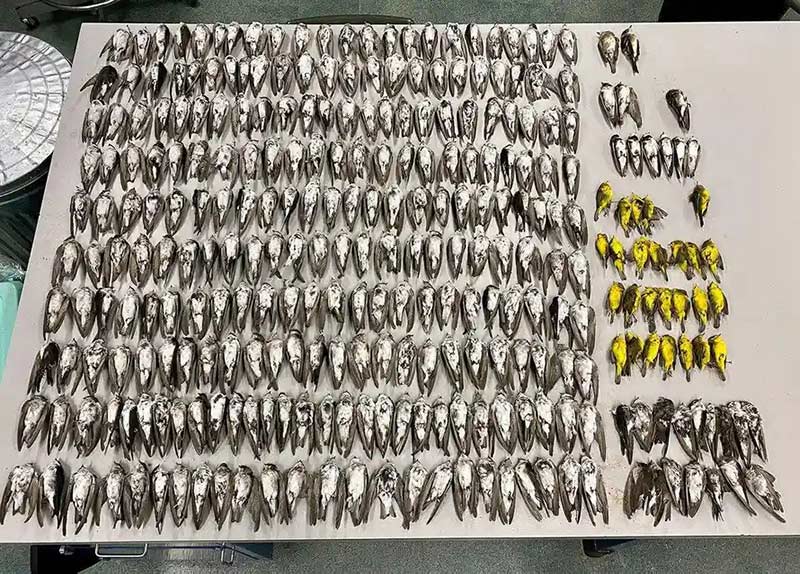

250 Violet-Green Swallows and 35 Wilson's Warblers collected along the Rio Grande in Velarde, New Mexico, in September, 2020 (photo: Jenna McCullough, University of New Mexico)

12/26/2020 Mass die-off of birds in south-western US 'caused by starvation' by Phoebe Weston, The Guardian

- Necropsy reveals 80% of the thousands of songbirds that died suddenly showed typical signs of emaciation

-

Birds ‘falling out of the sky’ in mass die-off in south-western US

-

Read more in our series Biodiversity: what happened next?

12/23/2020 Sugary Drinks May Be Bad for Aging, By Nicholas Bakalar, The New York Times

Consumption of both sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened drinks was tied to an increased risk for frailty in women over 60.

11/27/2019 Climate tipping points — too risky to bet against, By Timothy M. Lenton, Johan Rockström, Owen Gaffney, Stefan Rahmstorf, Katherine Richardson, Will Steffen & Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, Nature

The growing threat of abrupt and irreversible climate changes must compel political and economic action on emissions.

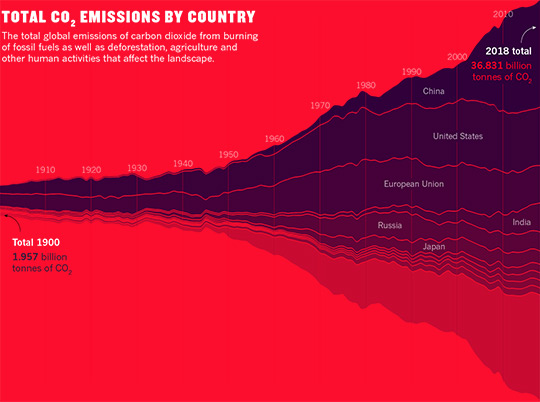

9/18/2020 The hard truths of climate change — by the numbers, By Jeff Tollefson, Nature

A set of troubling charts shows how little progress nations have made toward limiting greenhouse-gas emissions.

9/13/2019 ‘Ecological grief’ grips scientists witnessing Great Barrier Reef’s decline, by Gemma Conroy, Nature

Witnessing the Great Barrier Reef “go into meltdown in the space of a week” in early 2016 was a major shock for David Suggett, a coral physiologist at the University of Technology Sydney. “Nothing can prepare you for seeing it play out in real time,” he says.

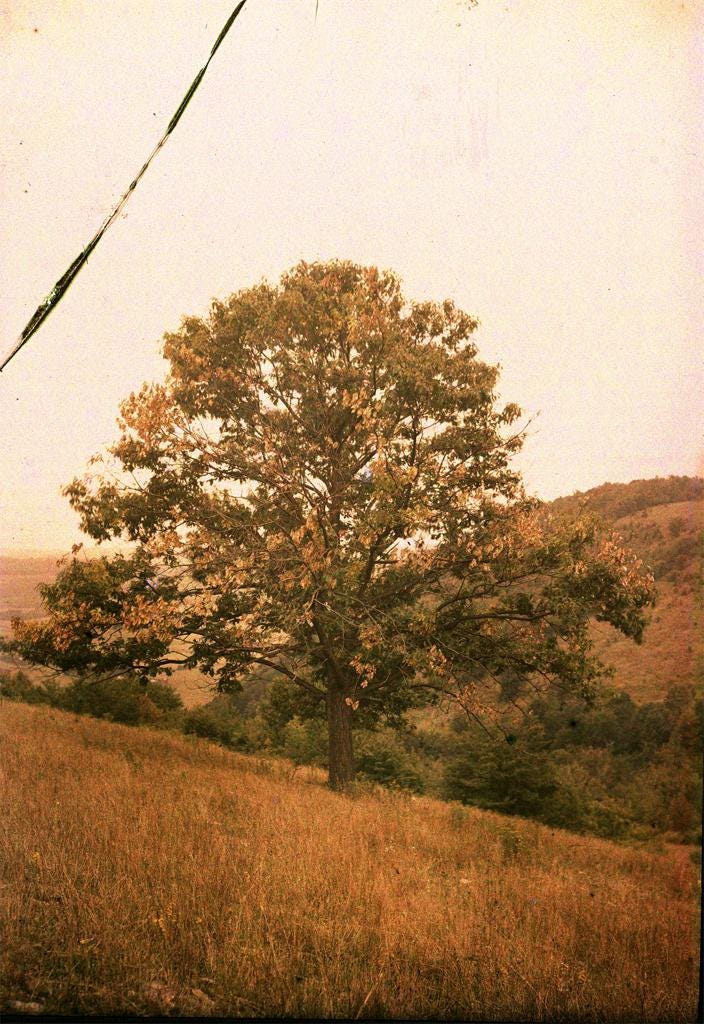

A dying chestnut tree photographed in 1916 in North Spencer, New York. (Cornell University)

1/25/2017 There used to be 4 billion American chestnut trees, but they all disappeared, by Heather Giligan, Timeline

The combined powers of the public, scientists, and the governments weren’t enough to save the chestnuts. The loss was stunning, both financially and emotionally. “Efforts to stop the spread of this bark disease have been given up,” The Bismarck Daily Tribune resignedly reported in 1920. The paper estimated that the value of the trees was $400,000,000 as recently as a decade before. The kings of the Eastern forest now die as shrubs.

2017 Dos and Don'ts of Public Rights of Way on the British Isles, Ireland and Scotland

In the UK, people have the ancient legal right to cross another person's property without fear of being gunned down by the land owner.

FAQ: public rights of way in England and Wales

As you can see from the reporting in Open Space magazine, keeping the right requires struggle.